Today was the birthday of the map of Germans from Russia Settlement Locations. It was created in 2016 and had 103 villages on it.

I often think about all the technology behind this project and am both grateful and giddy that so much of it happened in my lifetime. Things started coming together in the 1990s when I was fresh out of college. I have two BAs from New Mexico State University in English and Journalism & Mass Communications. I’ve not used either professionally aside from a brief time employed as a technical writer right out of college. Computers and networking were much more interesting, and even though I worked at a newspaper once, I was in the production department tending to the old mainframe, the new Unix-based digital photo delivery system, encouraging the use of computer pagination over manual paste up, and trying to convince anyone who would listen that online news was the future. They were not ready for the future. But I was. Like most who were in what would become to be known as “Information Technology,” I bounced around at jobs, sucking the marrow out of each one and keeping notes about everything I learned. Back then, there wasn’t a degree that prepared you for real IT jobs. Technology was happening too fast, and it was thrilling to be bobbing up and down in those waves. I did stints at both universities (nurturing environment but underfunded) and commercial companies (plenty of money for tech but no sleep for me). I sailed through the dot-com bubble easier than anyone should have. Always employed, always learning, and always having fun.

Most of the technology used in this project to locate ancestral colonies, map them, and make them available on the internet wasn’t available to civilians, wasn’t reliable, or didn’t exist in 1994 when I started researching my own family. Without going in too deep, here are just a few:

- Aerial & satellite imagery – geboren 1858-1972

- Global Positioning System – geb. 1973

- The Internet – geb. 1960s-1980s (.gov and .edu), geb. 1990 (commercial .com)

- World Wide Web – geb. 1989 (text only), geb. 1993 (graphic web browser)

- Google – geb. 1998

- Keyhole Earth – geb. 2001

- Google Earth – geb. 2004

- Google Maps – geb. 2005

- Google My Maps – geb. 2007

- Georeferencing – geb. ~2008

Aerial & Satellite Imagery

In the mid-1800s, images were taken from hot air balloons. This originated in Paris by French photographer and balloonist Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, known as “Nadar”, in 1858. As soon as photography was available circa 1826, humans had an itch to get a birds-eye view of their surroundings.

|

Honoré Daumier, Nadar Elevating Photography to the Height of an Art,

1862, lithograph from Souvenirs d’Artistes. National Gallery of Art |

Beginning in the early 1900s, images were taken from airplanes. Crop dusters were used at first, but as aeronautics advanced, military planes were outfitted with cameras for reconnaissance missions.

|

Barnstormer Jersey Ringel with a camera on top of the wing of an airplane in flight. 1921. Library of Congress

|

In 1946, images began to be taken from suborbital flights. This time rockets were outfitted with cameras.

|

View of Earth from a camera on the rocket V-2 #12, launched October 24, 1946. White Sands Missile Range/Applied Physics Laboratory. Smithsonian Magazine

|

The first satellite image was a crude image of of a sunlit area in the Central Pacific Ocean with cloud cover. It was taken August 14, 1959.

In July of 1972, the U.S. launched the Landsat program to capture satellite imagery of Earth. The program is still running today with the latest satellite, Landsat 9, launched in late 2021. Yesterday (February 10, 2022), Landsat 9 data became publicly available for researchers. Millions of images have been taken and archived and are all viewable through the U.S. Geological Survey Earth Explorer website.

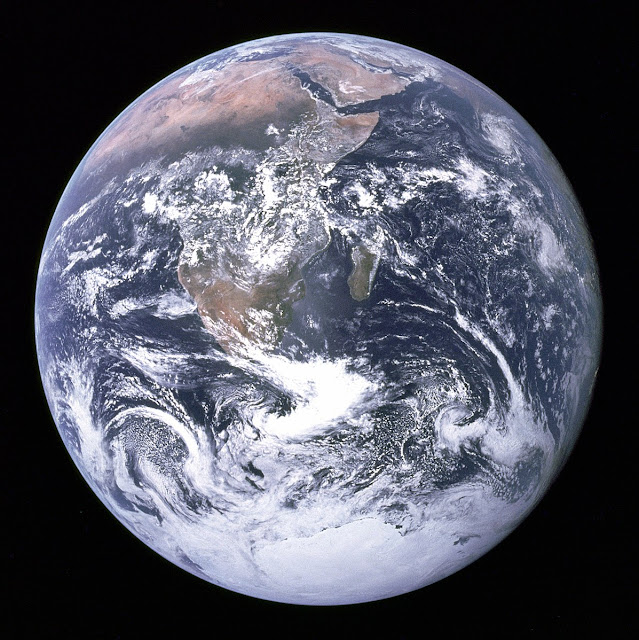

Later that year, “The Blue Marble” was taken from Apollo 17 on December 7, 1972.

|

Earth as it was seen from Apollo 17, December 7, 1972. Wikipedia

|

These are some of the 6,500+ satellites orbiting the Earth right now, roughly 5,000 of which are active. This changes every two weeks or so with each SpaceX launch of its Starlink satellites.

Why does it matter?

- Global Positioning System uses satellites for exact positioning.

- Google Earth and Google Maps use satellite images and GPS.

- All of the above are needed to visually confirm the location of German colonies that have been destroyed or abandoned. Google Earth (full version) allows one to go back in time through available images.

As you can see, the evidence of this this colony, Sivushka, south of Orenburg, is disappearing with time.

|

| October 8, 2002 |

|

| July 20, 2004 |

|

| June 28, 2010 |

Global Positioning System (GPS)

GPS was built in 1973 by the U.S. Department of Defense for military use. It was called “Navigational Satellite Timing and Ranging Global Positioning System” or NAVSTAR GPS. It was a highly accurate navigation system to replace older systems that were affected by distance or the weather. It was for military only through the 1980s.

A commercial version available in early 1990s in the U.S., but it was not very accurate because of Selective Availability (SA). This was an intentional degradation of public GPS signals so that it was not as accurate as the military version.

I

n 2000, U.S. legislation did away with SA, and GPS accuracy for commercial use improved 10-fold overnight. The popularity of handheld GPS receivers increased. GPS is now in vehicle navigation systems, maps on smartphones, etc. The U.S. has 31 GPS satellites in its constellation. The EU’s Galileo has 28. Russia’s Glonass has 24. China’s Beidou has 50.

|

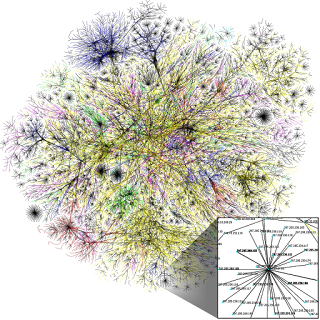

| Internet: a network of networks. |

The Internet

While satellite imagery and GPS were maturing, so was something called “The Internet.” This was a “network of networks” that allowed computers to talk to each other. It was initially used for sharing data among researchers in government and higher education institutions.

In the 1980s into the early 1990s, Internet protocols and applications became more “human” friendly, but everything was still text based. It was also small enough that if you were on it, you sort of knew where everything was. Still, there were early efforts to corral the information and make it easier to use.

- DNS – Number to name database (The name ahsgr.org is actually 162.242.142.236. Before they moved to their new website last December, it was 35.169.50.49. As a human, you didn't need to learn the new ip address. You kept using the name. The DNS server takes care of the translation from names to numbers for you.

- Email – Text-based, no graphics, no notifications, not mobile.

- Listserv – Subscription email list for communicating sharing information with groups. This was the beginning of the “drinking from the firehose” era of modern communication. Also, it was when I regularly started telling the librarians I worked with to please stop printing the internet.

- Content (No WWW yet, and I don’t remember actually using the term “content” at that point yet)

- FTP (used for uploading and downloading files; also a repository of said files)

- Gopher (menu-based content server)

- WAIS (text-based wide area information server)

- Archie (search engine for FTP sites)

In 1989, HTML (hypertext markup language) was invented. The following year, the internet became commercially available and the first browser arrived on the scene. The Lynx browser followed in 1992; it was still text based. No images.

In 1993, the Mosaic browser came out. It was the first web browser that could display images—verrrrry slowly, but it could do it! The first image I saw rendered was of Charon, Pluto’s moon, from a web server in NMSU’s astronomy department. Mosaic changed everything. This made the internet as a whole more attractive to everyone and commercially viable. It was not just for geeks anymore—pictures sold the internet to the public. Suddenly everything and everyone was going “on the net.” I spent several years around this time not only being a sysadmin but also teaching staff and students how to get onto the internet and how to use it for research.

And then along came ...

Google

In 1998, Google, Inc. was founded as an internet search engine company. It was not the first search engine on the scene, but today is currently the world’s most used.

Meanwhile, in 1991, a company called Keyhole, Inc. was stitching together and georeferencing satellite imagery from Landsat with funding from the CIA. They launched a site called Keyhole Earthviewer, which was a 3D interface to the planet using satellite images, aerial photography, and GIS data. Its target market: the real estate industry, urban planners, and travelers.

Google acquired Keyhole in 2004 and renamed Keyhole Earthviewer to Google Earth.

Google Maps launched in 2005, followed by Google My Maps in 2007. The idea behind MyMaps was to put map making into the hands of anyone so that they could “easily create custom maps with the places that matter to you.” The Germans from Russia Settlement Locations maps are made with Google My Maps. It wasn’t the first MyMap I made, but it is by far the largest and most complex in terms of the amount of data presented.

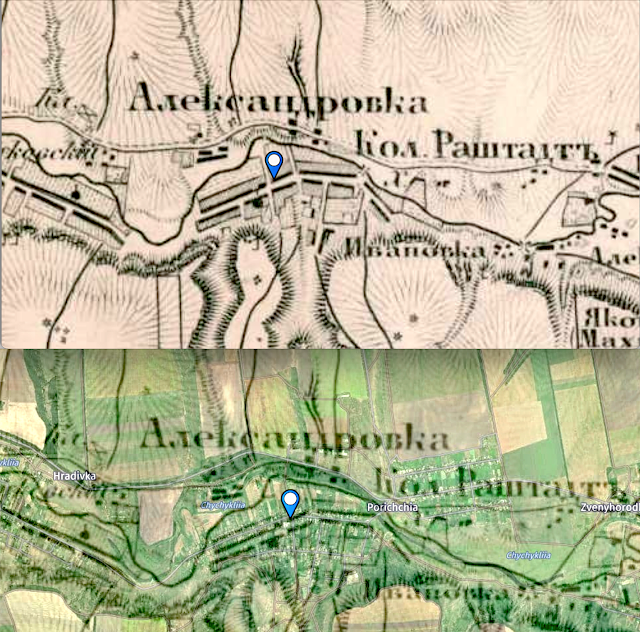

Georeferencing Meets History

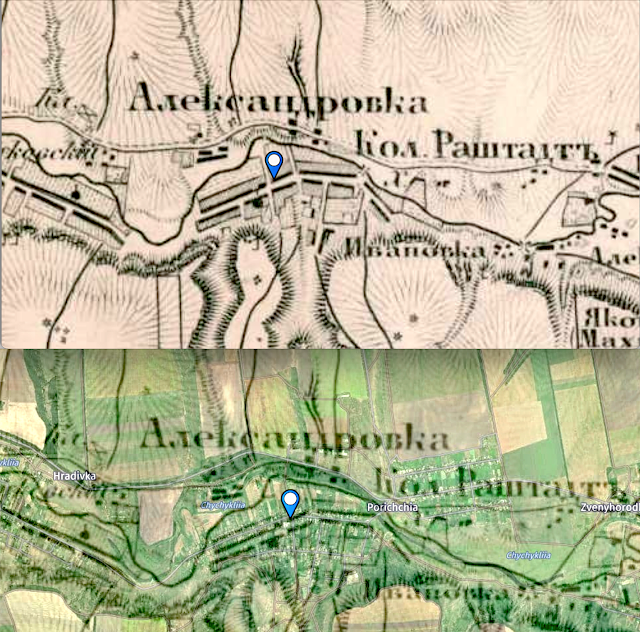

Simply put, georeferencing is applying geographic information to a digital image (aerial photos, satellite image, maps, etc.) so that the image is correctly placed in its real world location. The process (again, very simply) it overlaying a digital image—say a map of the Saratov province—onto a digital map such as Google Maps and then identifying several location points on the image that correspond with the map. The accuracy of the end result depends greatly on the accuracy and scale of the image, which is why many are done as tiles and stitched together as one big map. Hand drawn maps, such as those by Karl Stumpp, are not terribly accurate. Highly detailed military maps, such as those of the Austrian Empire and the Red Army, often produce great georeferenced maps. When all goes well, you can have a historical map or image overlaid on a current map where you can search for locations by today’s name or by GPS coordinates and see it on the historical map.

Georeferencing of historical maps seemed to start appearing on the web in early 2010s. There are many digital maps collections that are georeferenced and free to use. What this has brought about is the surfacing of old maps that have not been seen before. Using these maps helps me find lost ancestral colonies and also find my mistakes. Once the coordinates are nailed down, it’s fascinating wandering back in time through maps of a place as far as I can go and then viewing the satellite images available for it in the not so distant past.

|

1805—Rastatt (Beresan) before it was Rasatt

Curious. Will write more about this soon. |

|

1872—Rastatt

Top is the 1872 map. Bottom 1872 georeferenced map with modern map showing through. |

|

1920—Rastatt

|

|

1941—Rastatt

|

|

1985—Rastatt

|

|

2000—Rastatt

|

|

| 2012—Rastatt |

|

| 2021—Rastatt |

End of nostalgia trip. I hope that you have a new appreciation of all the technology it took for this project to be where it is today, what it took for you to be able to gaze nonchalantly at your ancestral colonies and say, “There it is. No biggie.” I am glad it’s no biggie. That means it has become a part of your everyday life. For some, this romp though time and technology of this will be familiar. For others, ancient history...making me also, somehow, ancient. I’m cool with that. No biggie.

###

Last updated 11 February 2022