Author’s note (tl;dr)—This map was inspired the article

“Goodbye Forever to Kleinliebental Near Odessa” (“Abschied für immer aus Kleinliebental bei Odessa”), an anonymously written account of the resettlement of the Germans living this village in the Ukrainian SSR to the Kazakh SSR in early October 1941.

In the course of my research to illustrate the article on a map, it became clear that the Kleinliebental in

the title of the article

did not match with

the location described in the article, and in the end was clearly

not the Kleinliebental near Odessa. I hesitated releasing the map. I didn’t want to add to the false impression of which Kleinliebental the article was about. It was not the neat and tidy package of a story I thought it would be about one village’s experience with deportation. But not all stories follow straight lines or clear paths, and there is nothing neat and tidy about “population movements,” as we’ve seen history repeat itself in this area in what seems like only yesterday. I decided that the story map was still worth sharing, even if it just provokes thought or conversation about the subject.

The comments and observations are my own and do not represent any of those who were involved in the writing, editing, translation, or publishing of the original article.

• • •

Farewell Forever Kleinliebental

“Equally shaken and surprised on the morning of June 22, 1941, our colony woke to the news of the onset of war. Those who still had bad memories of the First World War were in deep shock. All dreaded only the worst…”

From “Goodbye Forever to Kleinliebental Near Odessa”

When the Soviet Union entered the Great Patriotic War in June 1941, it ordered all Germans living in Russia to be deported east. This order could not be carried out immediately because of the immediate and strong advance of the German Wehrmacht. Instead, German-Russian men between the ages 16 and 60 years of age were deported first out of fear they might be used as additional soldiers by the Wehrmacht (this was a valid concern as this did happen) and also because they could be used by the Soviets as cheap labor to support the wartime effort. Even Germans already serving in the Red Army were discharged and sent to the Trudar or labor army by the end of the year.

“All Volga Germans ages 15 to 60 were mobilized in June 1941 and enrolled in labor battalions, while their families were deported to the Kazakh SSR and the Far East. About 1,500 to 2,000 Volga Germans forming two labor battalions were at No. 12 Vetlag camp [these were camps near Vetluzhsky, Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, Russia —SSP] during 1942-1943.”

1941 Deportation Timeline

Leading up to the winter of 1941, the following deportations of the German population in the Soviet Union took place. Initially they were carried out under the guise as resettlements or evacuations in order to protect the German-Russians from the approaching war, but soon they became forced population movements—deportations. The Germans who had lived in Russia for generations were not trusted by the Soviets, considered “unreliable,” sympathetic to the enemy, and even spies. But they were still human assets that could be exploited by the Soviets by sending them to remote parts of the country, both to the east and to the far north. This was nothing new to Russia. It had been going on since the time of the tsars and continues today.

According to Ulrich Mertens in his

German-Russian Handbook, “by 25 December 1941, 894,600 Germans were said to have been deported. This number increased to 1,209,430 Germans by June 1942.” Below are the deportations he lists for 1941 by month and region. There was an incredible amount of population movement during this time.

July

—Crimea: Between 4 July and 10 July 1941: The first mass deportation of German Russians was carried out here during WWII (approximately 35,000 German Russians until 20 August 1941; presumably altogether 65,000 German Russians). On 16/17 August 1941 (or after 20 August 1941): total forced migration, deportations to Ordzhonikidze [North Caucasus, former Tersk oblast] and the Rostov area; after the harvest (September - October 1941), approximately 50,000 people (together with German Russians from Ordzhonikidze) were deported to Kazakh SSR (in part Dzambul area).

— Dniepropetrovsk oblast: August to September 1941 (approximately 3,200 persons) were deported to the Altay region.

— Karelo-Finnish SSR: August 1941 deportation of Germans in to the Komi ASSR. [These Germans originated from the border areas of the Ukrainian SSR and had been deported in the early 1930s to the Karelo-Finnish SSR.]

— Odessa oblast: August to September 1941 (approximately 6,000 persons (?) but perhaps also fewer): deportations to the Altay region.

— St. Petersburg: Suburbs: August to September 1941: and only in part, deportations to Kazakhstan (Kyzyl-Orda, Qaraghandy, South Caucasus, Dzambul).

— Gorky oblast [former Nizhni Novgorod province]: deportations to the Omsk and Pavlodar oblasts; 3,162 Germans on 14 September 1941.

— Karbadino-Balkar [North Caucasus, former Tersk oblast]: September to October 1941: deportations to Kazakhstan.

— Krasnodar Krai [North Caucasus, former Krasnodar oblast]: September to October 1941: deportations to Dzambul oblast, in part to the Novosibirsk oblast; On 15 September 1941: 38,136 Germans.

— Kuybychev [Samara] oblast: September to November 1941: deportations to Altay.

— Moscow, city and oblast: 15 September 1941: 9,640 Germans were deported to the Karaganda and Kyzyl-Orda oblasts.

— North Ossetia [North Caucasus, former Tersk oblast]: September to October 1941: deportations to Kazakhstan.

— Novgorod oblast: September 1941: deportations to the Ivanovo oblast.

— Ordzhonikidze Krai [North Caucasus, former Stavropol Province]: September to October 1941: deportations to Kazakhstan (together with approximately 50,000 Crimean Germans); 77,570 Germans on 20 September 1941.

— Rostov oblast (together with approximately 2,000 Crimean Germans): September 1941: deportations to Altay Krai, Novosibirsk oblast, Dzambul oblast, Kyzyl- Orda oblast and South Kazakhstan oblast; 38,288 Germans from 10 to 20 September 1941.

— Russia, European: Beginning to middle of September 1941.

— Stalino oblast: September to October 1941: (only in part) deportations to Kazakhstan.

— Tula oblast: September to October 1941: deportations to Kazakhstan; 2,700 Germans on 21 September 1941.

— Volga German ASSR: From 3 to 21 September 1941: The deportation of approximately 366,000 (or 373,200) Germans via 151 (230?) transports by train from 19 different train stations (duration of the trip was four to six weeks) occurred after the edict on deportation of 28 August 1941 (see chronological table). Deportations to the oblasts of Akmolinsk, Aktyubinsk, Alma-Ata, Altay Krai, Dzambul, Qaraghandy, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Kustanai, Kyzyl-Orda, North Kazakhstan, East Kazakhstan, Pavlodar, Semipalatinsk, South Kazakhstan.

— Voroshilovgrad oblast: September to October 1941: (only in part) deportations to Kazakhstan. German Russians from recaptured areas of the Soviet Union.

— Zaporizhzhya oblast: September to October 1941: (only in part) deportations to Kazakhstan; 31,320 from 25 September to 10 October 1941.

— Zaporizhzhya-Mariupol-Melitopol, tri-city area : 28/29 September 1941: complete forced migration.

— Armenia [South Caucasus]: October 1941: deportations to Kazakhstan.

— Azerbaijan [South Caucasus]: mid-October 1941, together with Georgia, 25,000 Germans.

— Caucasus: deportations especially in October and November 1941; see also Crimea.

— Chechnya [North Caucasus, former Tersk oblast]: October 1941: deportations to Kazakhstan.

— Dagestan [North Caucasus, former Dagestan and Tersk oblasts]: October 1941: deportations to Kazakhstan.

— Georgia [South Caucasus]: mid-October 1941: deportations to Kazakhstan (together with Azerbaijan, 25,000 Germans) by way of Baku and the Caspian Sea.

— Industrial areas: October to November 1941: deportations to agricultural regions within corresponding settlement areas from where no deportations were otherwise carried out.

— Ingushetia [North Caucasus, former Terse oblast]: October 1941: deportations to Kazakhstan.

— Molotschna (area of Halbstadt) [former Taurida Province]: 3 October 1941: 15,000 Germans were deported to Siberia.

— Voronezh oblast: October 1941: deportations to the Novosibirsk oblast.

— Chita oblast [former Transbaikal oblast], strips near the borders: November 1941: deportations to the interior of the district.

About the Map

Often when I read material about Germans from Russia, I refer to the

Germans from Russia Settlement Locations map if places are mentioned in order to give me a sense of where the story was happening.

Such was the case three years ago while looking for articles to include in the

Germans from Russia Heritage Society’s publication

Heritage Review, I ran across one titled “Goodbye Forever Kleinliebental near Odessa” in the

Germans from Russia Heritage Collection. It was originally in German (“Abschied für immer aus Kleinliebental bei Odessa”) and published by the

Landsmannschaft Der Deutschen aus Russland in their 2001/2002

Heimatbuch. Alex Herzog had translated it, and it was a part of the extensive article collection at GRHC. The pending October 2020 issue of the

Heritage Review had other articles about Kleinliebental in it, and I thought it would be a good fit.

As I was proofing it to comply with the Chicago Manual of Style, I took note of all the places mentioned. It included the names of train stations, villages that they passed through, places where they had heard bad things were happening, where they finally crossed the Volga River, which railway line they were on at one point, etc. I thought it would make an interesting story map. I set the story aside for a later project.

Initially, I had planned to just include the places mentioned in the article, but in the years between when I originally read the article and just a couple of months ago, I decided that expanding it to show the bigger picture would be worth the effort. I ended up with four sections or layers on the map:

- Farewell Forever Kleinliebental

- Soviet Railways

- Occupied Eastern Front

- 100 Places of Exile

I recommend starting by

reading the article. It’s short, only five pages long. Then take a look at the map to see the story laid out by location. See the places mentioned in the article, where they started out, where they traveled by train, where the war was closing in around them, and where Germans from Kleinliebental near Odessa were eventually exiled.

1. Farewell Forever Kleinliebental

The first layer contains all of the locations mentioned in the article "Abschied für immer aus Kleinliebental bei Odessa" (Farewell Forever from Kleinliebental near Odessa) in the order of their appearance.

The over 40 locations mentioned and mapped on this layer include other German colonies, Jewish colonies, railway stops, rivers, towns and cities passed by while on the railroad, atrocities happening in nearby places, and areas with labor camps that were a part of the Gulag system.

Part of the article appears to be a first person account by a younger person who refers to their father early in the story. Other parts seem to indicate a deeper knowledge of German-Russians in the Soviet Union, and at one point mentioning an obscure study of Jewish colonies, which I’ll explain more in a bit.

There were some geographical problems with this story. Let me just start by addressing

the elephant on the map. The story states that “the front had already reached the Dnieper River just north of us, and the sounds of war had been clearly audible for some time.” When the time came for them to be evacuated, they packed horse-drawn wagons and headed in the direction of “the railway station Haitchur, about 70 kilometers [about 44 miles] away.” What was expected to take 12 hours took two days.

Haitchur was a railway station not near the city of Odessa but near the city of Zaporizhzhya across from the Dnieper River. Kleinliebental near Odessa was not south of or even near the Dnieper River.

How then, I wondered, were the Germans villagers led by Soviet authorities from Kleinliebental just outside of the city of Odessa on the Black Sea to a specific railway stop in the Zaporizhia oblast…548 kilometers (340 miles) away… by wagon… in two days…through at least some occupied territory? Logically, they were not. The village mentioned in the story could not have been Kleinliebental bei Odessa, but Kleinliebental bei somewhere else. Where it was, I am not sure. There are at least two possibilities in the Nikolaev and Stalino oblasts, but neither comes close to the distance from them to the railway station mentioned in the article.

Set aside the article title (most often in publishing the author of a story doesn’t write the headline) and the addition of the colony of Grossliebental to the list of villages they rode through (clearly added by someone other than the original author). The article should not be entirely discounted. It notes many historically accurate places to which Germans were deported in the 1940s. It also portrays the fear, uncertainty, and chaos experienced by the Germans as they were hauled, packed in freight cars, 5,466 kilometers (3,396 miles) to Western Siberia.

As for the Jewish colonies, when they arrived in Haitchur, “There were families from the Kankrin Colonies numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6…”

The Kankrin colonies were a subset of Jewish agricultural colonies established in the former Province of Ekaterinoslav that were the subject of a 1893 study by German-Russian Ivan V. Kankrin (1860-1917),

“Еврейские земледельческие колонии Александровского уезда” (“Jewish Agricultural Colonies in the Aleksandrovsky District”). Kankrin was reportedly a critic of the Jewish agricultural colonies. He insisted that they never did much agriculture work but remained artisans instead. He studied the 10 colonies in depth, and (inadvertently, I am sure) contributed a great deal of information about the colonies that descendants are now discovering as his work is translated. The colonies were located between the German settlements of the Molotschna Mennonite Colony and the German settlements of the Mariupol enclave.

They are not referred to anywhere else as “Kankrin colonies,” and I had to dig into the untranslated Russian-language study to even get the real names of each of them in order to locate them. The name Kankrin is not attached to any of them in Jewish genealogy.

It is curious that the term “Kankrin colonies” is used in the article. It indicates either the original author, or other writer who augmented the article, knew of the study some 40 years prior to the deportation story. While there is no doubt that Germans knew of neighboring Jewish colonies, would they have known about this study? The Kankrin study is not, as far as I can tell, a well-known part of the Germans from Russia history, and it nor the colonies are not mentioned in the standard literature or gazetteers. Feels like

a plant next to the elephant on the map.

If you have read this far (come for the maps, stay for the words), you can see why I hesitated going forward with releasing the map. I still believe there is value in it, and it may tell more of the story of the deportation of the other German colonies in this area at the same time, those in the Molotschna, Chortitza, Prischib and Mariupol areas. There may be a little something for everyone in it.

Is this layer accurate? I don’t know if I can judge it for accuracy beyond saying the story, as it was told, is mapped accurately.

2. Soviet Railways

This section of the map illustrates the railroad route the German deportees may have taken from the Gaichur (Haiture) railway station mentioned in the article. This station was east of the city of Zaporizhzhya, which had just been taken by the German Wehrmacht on October 3, 1941, the day after the Germans of Kleinliebental were rounded up to be “evacuated.” By October 8, 1941, both Melitopol to the southwest and Mariupol to the southeast were also taken by the Wehrmacht.

There were several clues in the article that made it possible to determine which railway lines they took in order to trace their journey:

— I knew where the frontline was at the time in early October in relation to the station where they were loaded onto freight cars., so I knew the directions they could not travel.

— I knew they crossed the Volga River near Kuibyshev/Samara, so they must have traveled north, and there were just a few places where they could have crossed the river.

— I knew the names of a few places they went through, which helped figure out which railway lines they traversed.

— I knew the name of one of the railway lines because it was included in the article.

— I knew where they left some freight cars behind, again helping to figure out on which lines they traveled.

— I knew where they ended up, the name of the train station and the village they were taken to after getting off the train.

Looking at a set of

1943 Soviet railway maps, I decided to work backwards from the destination station to the originating station simply because it was easier to get started and make progress going that direction. I marked up the maps, noted the connecting lines to the next map, and drew them on Google MyMaps line by line.

|

| Markup of the Tashkent railway map sheet showing connections to the Orenburg railway continuing to the northwest and the Turksib railway headed east. |

There is no evidence that they changed trains at any point when the railway lines changed. The line names were included to make it easier on me when drawing the lines on the map and also having them short enough so they did not get unwieldy. The railway lines show the real journey along current railroad tracks and not just a rough line from beginning to end. This is always a consideration when adding lines to Google MyMaps—the general route or the exact route. But in this case, there was no question that I wanted to show the actual journey as best I could. The bonus of doing this is that I was able to add up the distance. The length of the journey was approximately 5,466 kilometers (3,396 miles) and took 40 days, from October 5 through November 14.

Is this layer entirely accurate? Parts of it, yes, absolutely. Other parts were my best guess given the information I had.

3. Occupied Eastern Front

This section of the map shows cities in the Ukrainian SSR that were occupied in the region by October 1941. Each place has the name and the date it was taken by German or Romanian forces. I put these on the map when I was working on the first two sections to help me understand what was possible in terms of evacuation routes. At the end, I decided to leave them as a reminder of how close war was to the German colonies being evacuated and where it was already in full play.

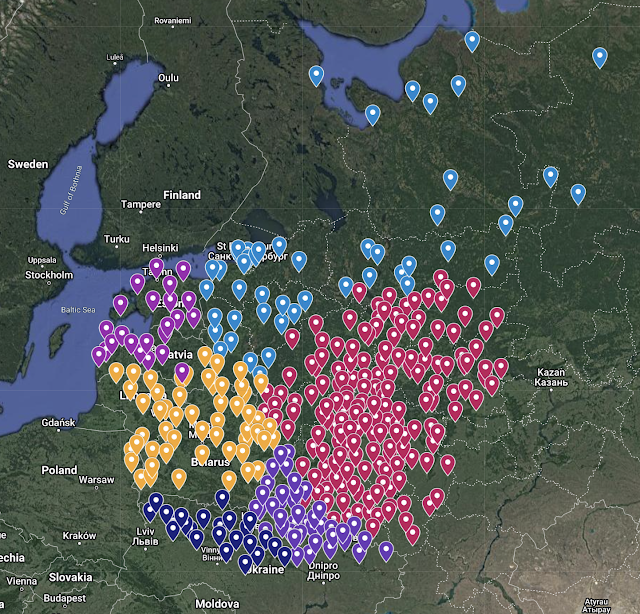

4. 100 Places of Exile

This section of the map is a compilation of 100 known locations to which residents of the colony of Kleinliebental near Odessa (again, not the Kleinlienbental in the article in the first section) were exiled/resettled/deported in the 1940s. It is unknown to me which railway stations or separation/filtration camps to which they were initially sent, but it shows how far and wide people were dispersed across not only the Far East, Siberia, and Central Asia, but also in central and northern European Russia. Approximately 500 people born between 1866 and 1937 were deported to over 100 places. I stopped at 100 for the sake of time spent on this project.

The information in this section was compiled from translated MVD (Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR) records obtained by both the

Glückstal Colonies Research Association (see GCRA’s

“2021 Data Drive” and by researcher Peter Goldade (see

“The Complete Works of Peter Goldade” website. These two sources were used because they were in electronic format, which made it easy for me to extract just the information about Kleinliebental and compile and analyze the data fairly quickly.

The GCRA data was more recently translated than the Goldade data, but it is notable that while there is some overlap between the two, the two sources are not identical. No dates were included in the translations, so it’s not known exactly when anyone was in these places other than sometime in the 1940s, during or after the war is unclear.

Both sources focus on the German enclaves in the Soviet Odessa oblast (Glückstal, Beresan, Liebental, Kutschurgan with a few from Bessarabia and other areas) and include full names, patronymics, birth year, birth place, family groups, and location of exile. The family groups show something that I want to call out: families were not always deported to the same place together. They were separated. And this was on purpose.

“The penalty of deportation is a carry-over from the times of the czar. By keeping this penalty the Soviet government had in mind not only the separation of criminal elements, those not giving a pledge of loyalty, and the scum opposing the political trend of the country, but also the colonizing of Siberia. Deportation is one way for untangling a difficult national problem. Siberia today presents a highly colorful mosaic of nationalities consisting of deported groups of ‘nationalists’ from the Ukraine, Poland, Orman, etc. There is also no shortage of Chinese, Koreans, and Japanese, creating a veritable tower of Babel which isn’t threatening to the USSR since the NZVD forements unofficial race hatred and prejudices which conforms to the so unproletarian device: divide et impera [divide and rule].”

The document continues on:

”Materially speaking, the government benefits in two ways: it protects itself from unwanted classes and it profits through exploitation of these classes for necessary labor. Siberia as the Soviet Arctic, and the boundless expanses of Soviet Central Asia, hide within themselves a vast natural wealth and the only way for the government to avail itself of this wealth is to populate these areas. It is a well known fact that deportation does solve this problem completely...”

Is this layer entirely accurate? Probably. The locations themselves are accurate. I fixed the coordinates on several of them from what was included in the source. As for who went where, I rely on the translations available. Neither source offered original-language images of the documents. Also, people from other villages in the same area of Odessa may have also been sent to some of these places. All of that will be reflected when these 100 places are fully documented and added to the

deportation locations map and layer on the main

German from Russia Settlement Locations map.

I need to be done with this map, and so I’m leaving it here. I hope you find it as interesting as I did.

Since you made it to the end of this very long post, this map can be turned into a presentation if there is any interest. Also, if you are interested in learning how to create a story map like this using Google MyMaps, I have developed a workshop that will be available next year.

# # #

Last updated 15 October 2023

.jpg)